It doesn’t take a Ph.D. to run a successful electroplating operation that has lasted 100 years and weathered the industry’s many storms.

Stephen SharrettsHowever, for Sharretts Plating in York, Pennsylvania, it is beneficial that the owner holds a doctorate in Business Administration, possesses advanced research skills, and is skilled in evidence-based business problem solving.

Stephen SharrettsHowever, for Sharretts Plating in York, Pennsylvania, it is beneficial that the owner holds a doctorate in Business Administration, possesses advanced research skills, and is skilled in evidence-based business problem solving.

Founded in 1925 as Charles D. Snyder and Son, Inc., the company has evolved from a small polishing and repair shop in Harrisburg into a cutting-edge surface finishing operation serving global industries.

For Stephen Sharretts, the company’s current CEO and third-generation leader, the story of Sharretts Plating is one of constant reinvention—grounded in family heritage but driven by forward-looking innovation.

He has mastered the art of identifying which manufacturing industries to enter to grow his company and which sectors to leave alone. His training — a Bachelor’s in Foreign Language and Business from the University of Pittsburgh, a Master’s in Global Strategic Communications from Georgetown University, and a Doctor of Business Administration from Drexel University — has prepared him to guide the company once led by his grandfather and then father through good and harsh times.

“We’ve always tried to prepare ourselves for tomorrow and give ourselves the tools to be successful,” Sharretts says. “The challenge has always been knowing where to play and how to win at the end of the day.”

Sharretts Plating provides standard copper, tin, nickel, and electroless nickel finishes, as well as gold, silver, platinum, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium.

Sharretts Plating provides standard copper, tin, nickel, and electroless nickel finishes, as well as gold, silver, platinum, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium.

A Century of Growth and Adaptation

Sharretts Plating specializes in alloys and finishes that most finishing operations prefer to ignore for obvious reasons: the difficulty of mastering the processes, and the costs often associated with precious metals. It provides standard copper, tin, nickel, and electroless nickel finishes, and also works extensively with gold, silver, platinum, palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, and numerous other precious metals.

EN-plated polycarbonate connectors.The company’s origins date back to the early 20th century, when Harrisburg’s metal finishing industry primarily served the state capital and surrounding manufacturers. Sharretts’ grandfather joined the business as a teenager in the late 1930s and returned to it after serving in Europe during World War II.

EN-plated polycarbonate connectors.The company’s origins date back to the early 20th century, when Harrisburg’s metal finishing industry primarily served the state capital and surrounding manufacturers. Sharretts’ grandfather joined the business as a teenager in the late 1930s and returned to it after serving in Europe during World War II.

“Charles Snyder promised him and many others that when you come back, your job will still be there,” Sharretts says.

As manufacturing boomed across South-Central Pennsylvania in the post-war years, the company became a top supplier to emerging connector and electronics firms, such as Tyco Electronics, Amphenol, and Molex.

“It also helped that my grandfather was schoolmates with a lot of the people who became the president, chairman of these corporations now that they’re in Harrisburg,” Sharretts says. “He had a natural in, and we became a top 2%, tiered supplier to companies like Tyco and their partners, for nearly 50 years.”

By the 1980s, under the leadership of Stephen’s father and uncle, Sharretts Plating expanded into York, eventually consolidating operations there in a 50,000-square-foot facility that continues to grow and evolve.

The Next Generation: From Tradition to Technology

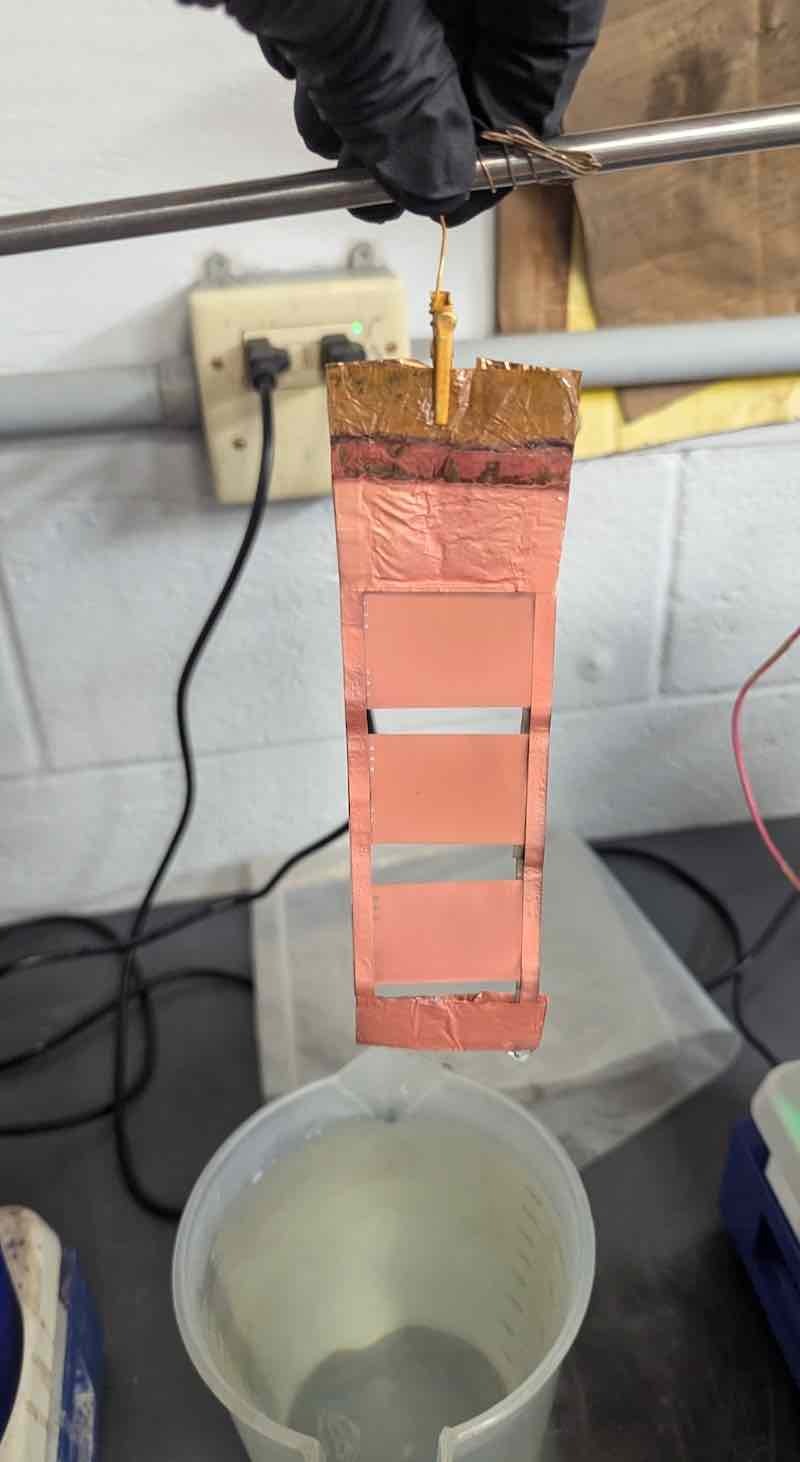

Copper plating step on flexible cearmic wafers.Sharretts officially entered the business in the early 2000s after earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh and finishing with a doctorate in business administration from Drexel University in 2020 — an education he says helps him approach management and decision science strategically.

Copper plating step on flexible cearmic wafers.Sharretts officially entered the business in the early 2000s after earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh and finishing with a doctorate in business administration from Drexel University in 2020 — an education he says helps him approach management and decision science strategically.

“It’s not about touting credentials,” he explains. “It’s basically the tools and the education that allow me to make better decisions financially and about how we grow our business in the different opportunities that are beyond the normal. And what I mean by that is, where to play and how to win at the end of the day. If I’m trying to compete with a hundred different metal finishers on the very same finish, it’s all about price and delivery, and it’s a race to the bottom.”

That mindset has guided the company through several key transformations. While traditional plating on steel, copper, and aluminum remains part of its portfolio, the company has increasingly focused on what Sharretts calls “the holy trinity” of advanced finishing: plating on plastics, ceramics, and refractory metals such as titanium, tungsten, and molybdenum.

“While we still offer finishing on traditional substrates, the trend is towards the new technology that requires these exotic materials,” he says. “Whether it be for thermal stability, dielectric reasons with ceramics, plastics for lightweight, or low-cost manufacturing that still need the coating for a functionality, those are the things that we’re seeing the growth area in.”

Pushing Boundaries: Plating on Plastics and Beyond

Sharretts Plating began experimenting with plating on plastics in the late 1970s — long before the process became widely viable. But in the last decade, the company has invested heavily in greener, more sustainable R&D efforts to make the process both reliable and environmentally responsible.

EN-plated nylon cloth.“We’ve invested over a million dollars into R&D to make plating on plastics less dependent on harmful acids like chromic acid,” Sharretts says. “It’s a high-mix, low-volume type work, and it’s not the plating on bumpers or the trim for vehicles and that type of parts. It’s the things that would be traditionally made out of aluminum and copper.”

EN-plated nylon cloth.“We’ve invested over a million dollars into R&D to make plating on plastics less dependent on harmful acids like chromic acid,” Sharretts says. “It’s a high-mix, low-volume type work, and it’s not the plating on bumpers or the trim for vehicles and that type of parts. It’s the things that would be traditionally made out of aluminum and copper.”

Part of that push dates back to the 1980s, when Sharretts would travel with his father all over the country — and later around the world — to visit metal finishers. They formed close relationships with several European companies, including one in France with multiple locations across Europe that is primarily known for zinc and zinc-alloy finishing and hot-dip galvanization. They still have that relationship even today.

“As a result. I’m bilingual in French and have worked in their facilities in Europe for a few years and seen the technology,” Sharretts says. “It was really opening, eye-opening for me to see what it’s like in a different economy and what they’re up against.”

“We can’t have people pointing the finger at each other, saying, ‘They didn’t do their job’ or ‘I didn’t do my job.’ It creates cross-pollination so that everyone’s accountable at the end of the day. And if something’s wrong, then it’s about not continuing without stopping and finding the problem.”

This focus on innovation extends to precious and platinum group metals (PGMs), such as platinum, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium, which are increasingly used in the semiconductor and power generation markets.

“We pride ourselves on material preparation,” Sharretts says. “Our slogan is ‘Surface Treatment Experts’ because the underlying emphasis is how do you prepare these materials so you can put whatever you want on them.”

A Modern Approach to Management and Workforce

The company was among the first metal finishers in the U.S. to achieve ISO certification in the 1990s.At its peak in the 1990s, Sharretts Plating employed more than 200 workers across two facilities. Today, with automation and advanced process controls, that number sits closer to 55. Yet, Sharretts notes, the workforce is more skilled and cross-trained than ever, a business acumen that his father implemented.

The company was among the first metal finishers in the U.S. to achieve ISO certification in the 1990s.At its peak in the 1990s, Sharretts Plating employed more than 200 workers across two facilities. Today, with automation and advanced process controls, that number sits closer to 55. Yet, Sharretts notes, the workforce is more skilled and cross-trained than ever, a business acumen that his father implemented.

“We have a team that he started grooming a long time ago,” he says. It was about upskilling people and sending them out for continued education. This initiative began in the 1990s, driven by our desire to be self-sufficient, particularly in areas such as analyzing our chemistries and related practices. We didn’t want to rely on the chemical companies to come in and do it for us.”

The goal is to achieve duplicity and coverage in every facet of their business, whether it be environmental, such as wastewater treatment, or maintenance-related activities, and even to train line operators in titration analyses.

“We can’t have people pointing the finger at each other, saying, ‘They didn’t do their job’ or ‘I didn’t do my job,’” Sharretts says. “It creates cross-pollination so that everyone’s accountable at the end of the day. And if something’s wrong, then it’s about not continuing without stopping and finding the problem.”

“If you look at a 50-year trend back from 1977 to present, about 30 metal finishers per year go out of business. The writing on the wall to me is when you see all the private equity groups and their peers trying to solicit you constantly every day.”

The company was among the first metal finishers in the U.S. to achieve ISO certification in the 1990s and received a Best Manufacturing Process Award from the U.S. Navy for its closed-loop wastewater treatment system. Environmental responsibility, Sharretts emphasizes, has been part of the company’s DNA for decades.

Preparing for the Future: Semiconductor Expansion

Stephen Sharretts says his company will look to achieve further diversification in the years ago.Looking ahead, Sharretts Plating aims to increase its presence in the semiconductor market, which demands extreme precision and cleanliness. The company is developing new cleanroom environments and acquiring specialized expertise to meet these stringent standards.

Stephen Sharretts says his company will look to achieve further diversification in the years ago.Looking ahead, Sharretts Plating aims to increase its presence in the semiconductor market, which demands extreme precision and cleanliness. The company is developing new cleanroom environments and acquiring specialized expertise to meet these stringent standards.

“It’s not going to take over our focus; however, it’s a good diversification for us,” he says. “We’re investing in the future. You can always have a foot in both the present and the past, but we’re always looking ahead to the next step and preparing for what tomorrow holds.

Sharretts is candid about the broader challenges facing the finishing industry — particularly consolidation and the growing presence of private equity. He laments that, for far too long, finishers have all been trying to do the same thing in their processes, and as a result, the industry is contracting at rates most don’t fully realize.

“If you look at a 50-year trend back from 1977 to present, about 30 metal finishers per year go out of business,” Sharretts says. “The writing on the wall to me is when you see all the private equity groups and their peers trying to solicit you constantly every day.”

He says he has seen quite a few peers sell to large equity groups lately.

“It’s astonishing, and what it tells me is these are very successful companies, but the industry is contracting,” Sharretts says. “And I think a lot of us have hit a crescendo or a wall where we can’t really grow organically much longer.”

He says one of the main reasons is that family-owned companies require significant capital to reinvest in their businesses.

“We don’t have it, or we can’t get access to it,” Sharretts says. “And that’s where these equity groups are really providing that ability. It is the expression in Washington: if you are not at the table, you are what’s for dinner. And, I’m afraid that’s what’s happening to a lot of our peers in the industry; while they do well, they never get big enough to where they have enough clout to have leverage with the tier one OEMs or the tier twos.”