The electrochemical anodization of stainless steels enables the fabrication of nanostructured oxide layers with high corrosion resistance and tunable functionality.

Compared with conventional valve metals such as aluminum or titanium, stainless steels present greater complexity due to their multicomponent composition and stable passive films. Recent progress, including dual-step anodization, optimized electrolytes, and targeted post-treatments has made it possible to form robust, self-organized nanoporous oxides with controlled morphology and thickness.

Compared with conventional valve metals such as aluminum or titanium, stainless steels present greater complexity due to their multicomponent composition and stable passive films. Recent progress, including dual-step anodization, optimized electrolytes, and targeted post-treatments has made it possible to form robust, self-organized nanoporous oxides with controlled morphology and thickness.

This review critically evaluates these advances, highlighting how processing parameters influence oxide composition, pore ordering, and long-term corrosion performance. The discussion integrates recent mechanistic insights with practical design strategies for catalytic, energy-storage, and protective applications.

Remaining challenges related to phase stability, mechanical integrity, and scalability are identified, along with future opportunities for deploying anodized stainless steels in advanced electrochemical and energy systems.

Original title: Electrochemical Anodization of Stainless Steels: Advances in Nanostructured Oxide Synthesis for corrosion-resistant and functional surfaces

1. Introduction

Electrochemical anodization is a widely used surface modification technique that enables the controlled growth of oxide layers on metals by applying an external voltage in a suitable electrolyte. The functional properties of nanostructured materials are strongly affected by structural parameters such as pore size, depth, and interpore distance. Therefore, fabricating highly ordered and precisely controllable nanostructures is essential for enabling a range of practical applications. While anodization has been extensively optimized for valve metals such as aluminum [1,2], titanium [[3], [4], [5]], and tantalum [6,7], yielding thick, stable oxides like TiO2 layers up to 100 μm. These systems are characterized by “valve” behavior, conducting current in one direction and allowing precise control over oxide growth and properties [8,9]. These materials, characterized by their high surface area, mechanical strength, and chemical stability, are particularly beneficial for applications in corrosion protection [10,11], catalysis[12], Energy storage and conversion [13], and biomedical implants [14]. Recent years have seen increasing interest in extending these benefits to non-valve metals like stainless steels [9,15,16].

Stainless steels, defined by a minimum of ∼10.5 wt % chromium content, are corrosion-resistant alloys that form a passive oxide layer under ambient conditions. They are broadly categorized into five families based on their microstructure: austenitic, ferritic, martensitic, duplex, and precipitation-hardened stainless steels. Austenitic grades such as AISI 304 and 316 are the most widely used due to their excellent corrosion resistance (pitting potentials >300 mV in chloride media), ductility, and weldability. Grade 304 contains approximately 18–20 % chromium and 8–10.5 % nickel, offering good resistance in oxidizing environments. Grade 316 includes 2–3 % molybdenum, which enhances its resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion, especially in chloride-rich media. Ferritic grades are magnetic and chromium-rich but lack nickel, while martensitic and duplex grades offer tailored combinations of strength and corrosion resistance for more specific applications [17,18]. The standard chemical composition of the two most widely used austenitic grades, 304 and 316, is presented in Table 1

Table 1. The standard chemical composition (in wt %) of AISI 304 and AISI 316 austenitic stainless steels, as specified by the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI), shows the maximum values for each alloying element.

| AISI Number/Grade | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Mo | Ni |

| AISI 304 | 0.07 | 0.75 | 2.00 | 0.045 | 0.030 | 17.5/19.5 | - | 8.0/10.5 |

| AISI 316 | 0.08 | 0.75 | 2.00 | 0.045 | 0.030 | 16.0/18.0 | 2.00/3.00 | 10.0/14.0 |

Stainless steels are key structural materials in environments that demand long-term corrosion reliability. In the nuclear industry, austenitic grades such as 304 L and 316 L are used in reactor systems and heat exchangers exposed to high temperature and radiation [[19], [20], [21], [22]]. In marine engineering, they are used in seawater pipelines and offshore structures that are prone to chloride-induced attack [23,24]. These applications require surfaces with high corrosion resistance, mechanical integrity, and stability under aggressive conditions, motivating the development of advanced anodization approaches to enhance and functionalize protective oxide layers.

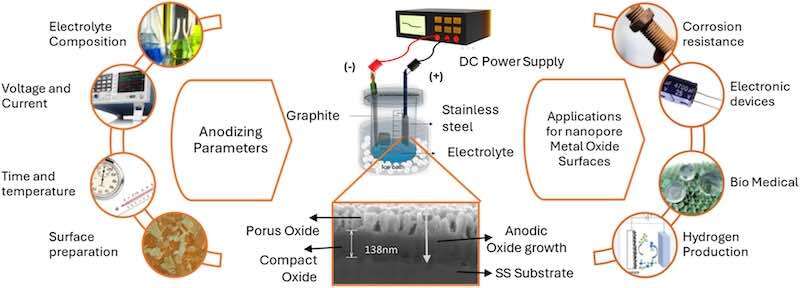

While their spontaneous passive films provide good protection, they are typically thin (2–5 nm) and lack the tailored nanostructure or advanced functionality possible through anodization. Adapting anodization techniques, initially developed for valve metals, to stainless steels presents both challenges and opportunities for multifunctional material development (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A schematic illustration of the anodization process for stainless steel shows key anodizing parameters, the electrochemical cell setup, and the formation of compact and porous oxide layers. The applications of nanoporous anodic oxide structures in functional and corrosion-resistant surfaces are also highlighted.

The engineering and manipulation of passive films on stainless steel have long underpinned efforts to enhance their corrosion resistance, stability, and functional surface properties for diverse applications, from decorative coloring to advanced engineering systems. Established chemical oxidation routes, such as the INCO process, wherein stainless steel is immersed in a mixture of sulfuric and chromic acids at elevated temperatures (typically H2SO4/CrO3 at 70–80 °C), set a benchmark for interference coloring and surface durability, and can reproducibly produce oxide layers of 40–100 nm in thickness, colored film [25,26].

Building on these foundations, early electrochemical approaches focused on nanostructuring the surface of stainless steel. Pioneering work by Vignal et al. [27]. and Martin et al. [28]. demonstrated that electropolishing in perchloric acid-based organic electrolytes could yield highly ordered dimple-like and quasi-hexagonal nanostructures on austenitic stainless steels (e.g., AISI 316 L, AISI 304 L). These patterns, with cell periodicities (center-to-center distances) ranging from ∼90 nm to 230 nm and dimple depths of 5–20 nm, are controlled by electroconvection processes and independent of grain orientation, highlighting the fundamental role of mass transport and bath conditions in nanostructure formation. Such strategies established the potential for precise surface patterning and functionalization [29].

Progress in electrochemical anodization introduced pulsed and square-wave potential polarization in acidic electrolytes, producing porous oxide films, mostly on SS304 and SS316L, but initial layers were generally thin (<300 nm) [30]. Together, parallel interest in pure iron substrates, driven by the low cost and visible-light-active band gap (∼2.1 eV) of hematite (Fe2O3), motivated researchers to pursue further anodization of stainless steels for combined corrosion protection and functional nano structuring [29,31,32]. Notably, Zhan and collaborators demonstrated visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation efficiencies up to 87 % on anodized SS304, showing multifunctionality alongside corrosion resistance [33].

Subsequent efforts targeted thicker, more robust, and highly ordered oxide films. Direct current anodization in fluoride-containing organic electrolytes (e.g., ethylene glycol or glycerol with 0.1–0.2 M NH4F and 0.1–0.3 M water) enabled the growth of self-organized nanoporous layers exceeding one μm thickness (often up to 3 μm, pore diameters 20–100 nm) on SS304 at 60–90 V for 1–3 hours [34,35]. Klimas and W. Lu [36,37] Refined this approach, extending it to super austenitic alloys (e.g., 254SMO, 904 L). Two-step anodization by Bowei Zang et. al [38] Allowed the fabrication of highly ordered, deep nanopore arrays (thicknesses up to 6 μm, pore depths 2–4 μm), a strategy previously used only for valve metals like titanium.

Recent advances include step-potential tailoring from the works of Wang et al. [39]., achieving ultra-thick (up to 17.5 μm), uniform nanoporous oxide films on SS304. Osada and Yanagishita [40,41] further optimized electrolyte composition and substrate pre-patterning to create highly ordered arrays on AISI 304, with interpore distances from 70 to 300 nm and aspect ratios up to 40. Teshima and Yanagishita’s recent work enabled wafer-scale (≥5 cm2) anodic oxide films with ordered pore arrangements, advancing applications in nanoimprint lithography, biosensing, and membranes [42].

Corrosion resistance remains central to these developments. Early studies by Jaimes et al. [43] found that as-anodized films on AISI 304 L, rich in fluoride and carbon, could be highly soluble and, without annealing, even less corrosion-resistant than bare steel (Icorr rising from ∼0.5 to 1.5 μA/cm2 in NaCl). Post-anodization annealing (350–400 °C, one hr.) stabilized the oxide and reduced Icorr to <0.15 μA/cm2. Saha et al. [44]. demonstrated that thermal treatment produces crystalline magnetite (Fe3O4) honeycomb structures on SS304, further improving corrosion performance. Functional surface modifications, such as those of Lee et al. [45]. “FLINO” fluorocarbon lubricant-impregnated coatings with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) yielded up to 99.99 % corrosion inhibition efficiency (percentage reduction in corrosion current density compared to bare substrate) in both liquid and vapor environments. Murmu et al. [46]. reported up to 92 % inhibition with hydrophobic SAMs on anodized SS304. Most recently, Choi et al. [47]. showed that thick barrier-type oxides on SUS316L, formed in NH4F-containing ethylene glycol, reduced corrosion rates by two orders of magnitude (Icorr from ∼2.4 to 0.02 μA/cm2) after 200 days in NaCl, with minimal pitting.

While the anodization of stainless steel has shown promise in areas such as electrocatalysis, photonics, and biomedical coatings, its role in enhancing corrosion resistance, an essential factor for long-term functional reliability, remains relatively underexplored compared to the well-established work on aluminum and titanium. Although many studies report improvements in corrosion behavior, these findings are often based on limited testing conditions, short-term immersion durations, and a lack of post-exposure surface analysis. This makes it challenging to generalize performance across environments. Furthermore, the mechanistic understanding of complex oxide growth, pore evolution, and microstructural factors, grain boundary effects, surface pre-treatments, and electrolyte-metal interactions remains insufficiently understood, highlighting the need for more systematic and application-driven investigations [48,49].

In this context, this review aims to provide a critical and structured overview of the anodization of stainless steels, focusing on nanoporous oxide layer formation and corrosion resistance enhancement. We begin with the fundamental electrochemical principles of anodization and discuss the challenges specific to stainless steel. This is followed by a detailed analysis of oxide growth mechanisms, the influence of key processing parameters, and current advancements in anodization techniques, including dual-step anodization, pre-patterned surface modification, and plasma-assisted methods. The review also explores the role of post-treatments such as heat annealing and surface functionalization in stabilizing the oxide structure and enhancing corrosion performance.

In the final sections, we critically assess reported corrosion resistance improvements, application areas, and unresolved questions. Through this synthesis, we aim to guide future research and support further development of anodized stainless steels as multifunctional materials, particularly in nuclear, marine, and biomedical environments where corrosion resistance, durability, and surface performance are critical.

2. Fundamentals of anodization and theoretical models

Electrochemical methods offer a cost-effective and scalable approach to synthesizing nanostructured oxide layers. By controlling the oxidation process in an electrolyte medium, anodization makes producing highly ordered nanoporous and nanotubular oxide structures possible. Electrochemical anodization, traditionally used for valve metals such as aluminum and titanium, involves subjecting a metal substrate, serving as the anode in an electrochemical cell, to a controlled external potential [50]. The cell typically comprises the metal (working electrode), an inert counter electrode (e.g., platinum or graphite), and an electrolyte containing reactive ionic species supporting oxide formation [51].

At the anode, the metal undergoes oxidation, releasing electrons and forming metal cations, which either dissolve into the electrolyte or react with oxygen-containing species such as hydroxide (OH-) or oxide (O2-) ions [52]. These oxygen species are generated through the anodic decomposition of water (Eq. 1).

2H2O → O2 + 4H+ + 4e- (1)

The fundamental reactions during anodization involve Metal oxidation and Oxide formation (Eq. 2–3)

M → Mn+ + ne- (2)

2Mn++ nO2- → M2On (3)

As the oxide layer grows, it begins to act as a dielectric barrier, impeding further ion migration and resulting in a reduction of current, unless pore formation or chemical dissolution occurs[53]. For valve metals, this dynamic interaction between oxide formation at the metal-oxide interface and simultaneous field-assisted dissolution by etching agents, like Fluoride ions (F-) at the oxide-electrolyte interface, facilitates the creation of highly ordered, self-organized porous structures [54]. Faraday's laws govern these phenomena. They are enabled by high electric fields (on the order of 105–107 V/m), which drive the outward migration of metal cations and inward transport of anions [55].

Insight into the kinetics of anodization is often obtained through current density-time (j-t) or voltage-time (v-t) transients under constant voltage (potentiostatic) or current (galvanostatic) conditions. A typical j-t curve, as shown in Fig. 2, comprises three distinct stages [44], which helps in understanding the underlying physicochemical events:

![Fig. 2. Schematic and current density-time (j-t) curve illustrating the key stages of nanoporous oxide growth during electrochemical anodization of metals. The diagram illustrates (I) the initial formation of a compact barrier oxide layer, (II) the onset of pore nucleation due to local field inhomogeneities, and (III) the steady-state pore growth. The current-time response is shown for a typical potentiostatic anodization process. Images have been redrawn with permission from the publisher[1].](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/2.jpg)

Fig. 2. Schematic and current density-time (j-t) curve illustrating the key stages of nanoporous oxide growth during electrochemical anodization of metals. The diagram illustrates (I) the initial formation of a compact barrier oxide layer, (II) the onset of pore nucleation due to local field inhomogeneities, and (III) the steady-state pore growth. The current-time response is shown for a typical potentiostatic anodization process. Images have been redrawn with permission from the publisher[1].

Stage 1: A significant decline in current density is noted due to the rapid formation of a compact, insulating barrier oxide. This layer continues to thicken over time, leading to increased electrical resistance. Classical models, such as those by Cabrera-Mott and Verwey, explain this behavior through ionic migration in the oxide, while more contemporary interpretations, like the point defect model and Lohrengel’s hopping mechanism, emphasize the role of structural imperfections in aiding ion transport [52]. Stage 2: Increased current density indicates the beginning of pore nucleation, resulting in a maximum local current. This phase represents the localized breakdown of the barrier layer and the development of an initial, disordered porous morphology. Stage 3: A steady-state regime is established, in which pore density stabilizes and growth becomes more uniform and vertically aligned. At this stage, the barrier layer thickness remains constant, while the porous layer continues to grow due to a dynamic balance between oxide formation at the metal-oxide interface and concurrent dissolution at the pore base[39,52,56]. Various theoretical models have been proposed to elucidate the mechanisms behind pore initiation and evolution observed in stages two and three in j-t curves, particularly for aluminum anodization. The earliest among them is by Keller et al. [57]., linked hexagonally arranged pores to a spherical distribution of electric field and localized Joule heating. Hoar et al. [58]. later, this was refined with the high-field ion transport model, suggesting that localized weakening of the electric field enables proton penetration into the oxide, reducing local resistance and enhancing oxide dissolution. Sullivan et al., through extensive TEM analysis, further emphasized that substrate-induced variations in oxide thickness and electric field strength play a significant role in pore formation, with Joule heating being a minor contributor.

More advanced interpretations include Thompson's hypothesis of “preferred sites” formed by electrolyte, oxide interactions, and Shimizu’s stress-driven nucleation model[59], which considers tensile stresses resulting from the Pilling-Bedworth ratio as triggers for oxide cracking and pore initiation. Conversely, Wu et al. and others have questioned the dominance of the field-assisted dissolution mechanism, highlighting the role of direct cation ejection in contributing significantly to the anodization current[60].

Although the exact details of pore initiation and growth during anodization remain under discussion, the field-assisted dissolution (FAD) mechanism is currently the most widely accepted model. According to this approach, a uniform oxide film initially forms under constant electric field strength. However, pore initiation arises due to local field inhomogeneities, typically caused by surface defects, metal protrusions, impurities, or prior surface treatments. These weak points facilitate localized dissolution and enhance current density, which results in localized heating (Joule heating), further accelerating the dissolution rate. As a result, pores begin to develop, and a dynamic balance is established between oxide formation at the metal-oxide interface and its dissolution at the oxide-electrolyte interface. This steady-state process leads to the continued propagation of the porous structure. Experimental observations by De Graeve and Lämmel et al. support the role of local heat effects in promoting this mechanism. An additional refinement to the FAD model involves the differential charge transfer at the metal/oxide (jmt/ox) and oxide/electrolyte (jox/el) interfaces. The local field strength governs the kinetics of ion migration across these interfaces and is described by,

j = jo exp(βE) (4)

where jo is the exchange current density, β is a constant, and E is the local electric field strength. Because the local electric field is generally stronger at the oxide-electrolyte interface compared to the metal-oxide interface, the condition jmt/ox < jox/el holds. To maintain current continuity across the interfaces (Imt/ox = Iox/el ), the system compensates by increasing the area of the metal/oxide interface, resulting in a curved geometry. This curvature is a direct geometric manifestation of the unequal charge transfer kinetics across the interfaces [2,58].

In parallel, an alternative hypothesis emphasizes the contribution of stress-driven material flow in oxide evolution. Radiotracer studies have shown that pore formation is not only a product of dissolution but also involves mechanical flow of oxide due to intrinsic stresses within the oxide film [[61], [62], [63], [64]]. These stresses, likely induced by the incorporation of anions during anodization, depend on the applied current density. Under certain conditions, internal stress is sufficient to cause lateral movement of oxide material. This view suggests that the oxide layer undergoes plastic deformation and internal redistribution, complementing the FAD model by accounting for structural reorganization beyond pure dissolution. Finally, the oxygen bubble mold model explains how oxygen bubbles, generated as a side reaction during anodization, influence the morphology of anodic oxide layers[65,66]. These bubbles act as molds for forming semi-spherical barrier layers at the pore bottoms. High-pressure regions beneath the bubbles, combined with elevated electric fields, promote plastic flow of the oxide from the pore base to the walls. Zhu et al. (2008) demonstrated that additional oxygen bubbles during growth can induce localized pore formation, resulting in serrated wall morphologies [66]. While the preceding models describe anodization behavior typical of valve metals, stainless steels deviate in thermodynamics, electronic transport, and film mechanics, as summarized below.

In contrast to valve metals such as Al, Ti, and Ta, which form highly stable dielectric oxides, stainless steels (Fe-Cr-Ni alloys) exhibit fundamentally different anodization behavior due to their non-valve nature. Oxides of valve metals, Al2O3 (Eg ∼ 8.7 eV), TiO2 (∼ 3.0–3.2 eV), and Ta2O5 (∼ 4–4.5 eV), are wide-band-gap insulators with low defect densities and strongly negative Gibbs free energies of formation (ΔG° ∼ −950 to −1100 kJ mol-1 per O2)[67,68].

These characteristics confine charge transport to ionic migration under a uniform high electric field, yielding compact, adherent, and self-limiting barrier layers. In stainless steels, however, the constituent oxides, Fe2O3 (Eg ∼ 2.1 eV, ΔG° ∼−500 kJ mol⁻¹ per O2), Fe3O4 (half-metallic, ΔG° ≈ −480), Cr2O3 (Eg ∼ 3.4 eV, ΔG° ∼ −740 kJ mol⁻¹ per O2), and NiO (Eg ∼ 3.8 eV, ΔG° ∼ −520 kJ mol⁻¹ per O2), have narrower band gaps, higher defect densities, and lower oxide stabilities [69]. The resulting films support mixed ionic, electronic conduction: while ions drive oxide growth at the metal/oxide interface, electron leakage through the film facilitates side reactions such as 2H+ + 2e- → H2↑ and partial reduction of Fe3+ → Fe2+ at the electrolyte interface[68,70]. These processes disturb the electric-field distribution, promote selective dissolution of Fe and Ni-rich domains, and generate compositionally graded, multiphase oxides rather than single-phase barriers. In addition, localized gas evolution and differential growth/dissolution create tensile stresses that, together with thermally induced and phase-transformation strains within Fe-oxide regions, lead to micro-cracking and delamination [[71], [72], [73]]. By contrast, the uniform, single-phase oxides of valve metals accommodate stress elastically and remain mechanically coherent. These distinctions in thermodynamic stability, electronic structure, and mechanical response explain why anodizing stainless steels demands more restrictive electrolyte and voltage control to emulate the self-organized oxide growth typical of classical valve metals.

Anodization is a highly tunable and scalable surface engineering technique that enables precise control over oxide morphology. However, information about translating the mechanisms established for valve metals to alloys like stainless steel, which possess complex phase compositions and passive behavior, demands a deeper mechanistic understanding. The following section explores anodization in stainless steels, focusing on the challenges, oxide layer characteristics, and corrosion performance of these multielement systems.

3. Stainless steel anodization

The anodization of stainless steel, especially austenitic grades like SS304, which will be discussed below, is increasingly studied for creating nanostructured oxide layers that improve corrosion resistance and other features. However, the electrochemical conditions across different studies vary greatly, making it difficult to establish a broad understanding of the underlying mechanisms. Most research has used the field-assisted dissolution model, initially developed for aluminum anodization, to explain oxide formation in stainless steel. Several studies have focused on anodizing austenitic stainless steels in mild acidic electrolytes, such as diluted sulfuric, nitric, or ammonium fluoride solutions, under constant voltage conditions [38,74]. These studies often interpret the underlying mechanisms based on physical characteristics observed through techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM), pore depth measurements, compact barrier layer thickness estimations, and chemical insights gained from X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS).

Initially, the native surface of stainless steel is protected by a thin, stable passive layer primarily composed of chromium oxide (Cr2O3), along with minor contributions from iron and nickel oxides. Upon applying the anodic potential, electrochemical oxidation of surface atoms is initiated. Chromium oxide reacts with water in an acidic environment to form hydrated chromium hydroxide (Cr(OH)3), as follows (Eq. 5)

Cr2O3 + 3H2O → 2Cr(OH)3 (5)

As the process continues, some Cr(OH)3 is further oxidized under the anodic potential to higher valence Cr(VI) species, such as CrO2(OH)2. This transformation is observed by XPS peaks shifting toward higher binding energies (∼578 eV), indicating the presence of Cr(VI) compounds [75,76]. Simultaneously, nickel on the surface is oxidized from its metallic form (Ni) to divalent nickel ions (Ni2+), which then react with hydroxide ions to form nickel hydroxide (Ni(OH)2)

Ni2+ + 2OH- → Ni(OH)2 (6)

This phase is detected in XPS spectra at approximately 855.5 eV. Iron also undergoes oxidation, first to Fe2+ and then to Fe3+, which precipitates as hydrated ferric oxide[17,77,78]. The O1s XPS spectra reflect the conversion of surface hydroxides to more stable oxides, with increased intensity at ∼530 eV corresponding to lattice oxygen (O2-).

Fe3+ + 3OH- → Fe(OH)3 → Fe2O3 + H2O (7)

The combined effect of these oxidation processes leads to the development of nanoscale surface features. Due to the relatively mild acidic strength and the moderate applied voltage, metal dissolution is limited, allowing surface roughening to occur via field-assisted ion migration rather than uncontrolled etching.

Differences influence this transition in the diffusion coefficients of metal cations within the oxide matrix. Chromium cations exhibit significantly lower diffusivity (D ≈ 10–20 cm2/s) than iron cations (D ≈ 10–15 cm2/s) at anodization-relevant temperatures in the oxide layer formed, leading to compositional stratification within the oxide film [39,75,80]. This diffusion disparity results in a layered structure, where a Cr-rich inner oxide is formed beneath an Fe-rich outer layer for the initially formed barrier oxide [81]. The application of an external electric field enhances cation migration, with iron and nickel ions preferentially diffusing outward while oxygen ions migrate inward. As this dense barrier layer forms, it impedes ionic diffusion, leading to a steep drop in current [82].

Pore initiation begins with pit formation on the barrier layer due to local electric field enhancement. These pits are deepened due to field-assisted dissolution at localized sites. As pits evolve into pores, a porous MOsF grows vertically. In a fluoride-containing acidic electrolyte, Fluoride ions play a critical role in pore nucleation by selectively attacking and dissolving Fe-O bonds, forming soluble Fe-F complexes [39,45]. Fluoride might primarily react with Fe, leading to Fe-F complex formation at a binding energy of ∼684.6 eV. Cr is comparatively less reactive due to the stronger Cr-O bonding, making it more dissolution-resistant than Fe [83]. This selective dissolution mechanism weakens the oxide structure at localized sites, allowing electric field-driven pore initiation and expansion. In addition, the solubility of Fe-F complexes in the electrolyte accelerates material removal, promoting the self-organization of nanopores (Eq. 3–5) [36,39,75]. As the anodization process progresses, the field-assisted dissolution mechanism governs pore evolution. Localized electric fields enhance ions' migration and oxides' dissolution at the pore base. The competition between oxide growth and dissolution determines the final pore morphology, with parameters such as voltage, electrolyte composition, and temperature influencing pore size and distribution [40,41].

Importantly, oxide growth occurs at the metal-oxide interface, while dissolution is active at the oxide-electrolyte interface. This dual-interface dynamic is governed by the short transport distance of oxygen ions and intensified electric fields at the pore base (Eq. 8–10). The dissolution front does not propagate strictly vertically; instead, it can deviate depending on local oxide composition and selective dissolution rates, resulting in irregular pore evolution. The mechanism of fluoride attack on oxides formed on stainless steel remains unclear. Unlike valve metals, where fluoride-rich regions are observed within the pore cross-section, similar features have not been reported for stainless steels.

Fe2O3 + 6F- + 6H+→ 2[FeF3]3- + 3H2O (8)

NiO + 2F- + 2H+ → NiF2 + H2O (9)

Cr2O3 + 6H+→ 2Cr3+ + 3H2O (10)

However, studies by Wang et al. indicate that the selective dissolution of elements such as Ni and Fe results in cross-linked, disordered pore structures in stainless steel, in contrast to the highly ordered, straight pores typically observed in other metals [39]. This mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 3, where disordered pore morphology arises from the preferential dissolution of Ni and Fe oxides within the oxide matrix. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that at higher anodization voltages, the intensified electric field at the pore bases enables uniform dissolution of all alloying elements, leading to cylindrical and more ordered pore morphologies [75]. Furthermore, following a similar dissolution mechanism, the two-step anodization method produces well-ordered nanopore arrays by promoting pore growth on pre-existing templates.

![Fig. 3. Schematic illustration and SEM characterization of nanoporous oxide formation on austenitic stainless steel by anodization. The process flow (top left) depicts the transformation of the substrate to a nanoporous anodic oxide film. SEM images show (a) the top view and (b) the cross-sectional morphology of the disordered nanoporous oxide layer after anodization for 5 min in electrolyte containing 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1 M H2O in EG (50 V at 20 °C). Bottom schematics (c, d) represent the random distribution of NiO and Cr2O3 phases within the Fe2O3 matrix before (c) and after (d) selective etching, highlighting electric field-assisted chemical dissolution of Ni oxides that guides pore development and leads to a disordered pore arrangement. Images adapted and modified with permission from the sources[39,79].](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/3.jpg)

Fig. 3. Schematic illustration and SEM characterization of nanoporous oxide formation on austenitic stainless steel by anodization. The process flow (top left) depicts the transformation of the substrate to a nanoporous anodic oxide film. SEM images show (a) the top view and (b) the cross-sectional morphology of the disordered nanoporous oxide layer after anodization for 5 min in electrolyte containing 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1 M H2O in EG (50 V at 20 °C). Bottom schematics (c, d) represent the random distribution of NiO and Cr2O3 phases within the Fe2O3 matrix before (c) and after (d) selective etching, highlighting electric field-assisted chemical dissolution of Ni oxides that guides pore development and leads to a disordered pore arrangement. Images adapted and modified with permission from the sources[39,79].

Annealing following anodization plays a crucial role in enhancing the properties of oxide films through two main mechanisms: the removal of fluoride ions trapped during the anodization process and the crystallization of initially amorphous oxide phases [84,85]. These transformations are generally associated with improved corrosion resistance. However, annealing can also pose certain risks, particularly the formation of cracks due to phase transformations in complex multi-element oxide systems. These transformations often lead to volumetric changes, either expansion or contraction, that generate internal stresses within the oxide layer. For example, the conversion of magnetite (Fe3O4, inverse spinel) to hematite (α-Fe2O3, rhombohedral corundum) involves structural rearrangement and a decrease in volume, which can induce microcracking.

Due to the complex multi-element nature of stainless-steel oxides, achieving well-ordered cylindrical nanopore structures is challenging, especially when selective dissolution and annealing-induced phase changes disrupt structural integrity. Cracks formed during these transformations may compromise the oxide layer's mechanical stability and protective performance. While improved corrosion resistance observed in accelerated tests may result from the increased surface area of the oxide layer, long-term corrosion behavior needs to be evaluated to draw definitive conclusions. Additionally, mechanical assessments, such as hardness and adhesion tests, are essential for assessing the robustness and substrate bonding of the formed oxide structures.

The exact mechanisms remain unclear, highlighting the need for further research to elucidate these processes. Despite this, experimental findings suggest that pre-processing and post-processing steps significantly influence the anodization outcomes. Anodization performed on pre-patterned or electropolished samples has yielded highly ordered pore structures, emphasizing the role of surface preparation in determining the final morphology [40,41]. To better understand these experimental trends, Table 2 summarizes the impact of various processing conditions, including pre-treatment methods, electrolyte compositions, anodization parameters, and post-heat treatment conditions, on the pore characteristics and microstructural evolution of anodized SS304 and SS316 grade stainless steel. These insights further highlight the complexity of the anodization process and the necessity of optimized processing strategies to achieve desired nanostructures.

Table 2. Summary of the influence of pre-treatment, anodization, and post-treatment processing steps on the morphological and microstructural characteristics of anodized austenitic stainless steels. The table details electrolyte compositions, process parameters, resulting pore morphologies, oxide thicknesses, and key literature references. Note - MP: Mechanical Polishing; EP: Electro Polishing; UC: Ultrasonic Cleaning; Anz: Anodization; HT: Heat Treatment; EG: Ethylene Glycol.

| Sample Grade | Processing Steps⁎ | Electrolyte Composition & Parameters | Pore Morphology | Microstructure | References |

| SS 316 L | MP - EP | EP: 10 vol.% HClO4 in EG (5 V to 100 V at 25°C for 15-300 seconds) | Pore Dia: 220 nm Depth: 14.3 nm | Image; table 1 | [27;28;34] |

| SS 316 | MP - UC - Anz1 - Anz2 | Anz1: 5 vol% HClO4 in EG (40-50 V at 0-10 °C for 10 min) Anz2: 0.3 M NaH2PO4 (5 V - 45 V at 0-10 °C for 10 mins) | Pore Dia: 85-120 nm Depth: 10 nm | Image; table 1 | [38] |

| SUS304 | EP - Anz1 - Anz2 | EP: 43 vol% H3PO4; 22 vol% H2SO4; and 35 vol% Glycerol (constant current of 0.5 mA cm-2 at 30 °C for 5 min) Anz 1&2: 60-100 mM NH4F in EG (30-50 V at 0 °C for 15-120 min) | Inter-pore distance: 47-63 nm Thickness: 1- 3 μm | Image; table 1 | [40;41;79] |

| AISI 316L | MP - UC - Anz1 - Anz2 - HT | Anz 1&2: 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1-0.2 M H2O in EG (50 - 90 V at 20 °C for 20 mins) HT: 400 °C for one hour in air | At 90V for 10 mins with 0.2 M H2O Thickness: ∼ 2 μm | Image; table 1 | [75] |

| SS 304 | UC - Anz - HT | Anz: 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1- 0.5 M H2O in EG (100 A m− 2 at 25 °C for 900 s) HT: 300-400°C for 30 mins | Thickness: 3-3.5 μm; Compact/Barrier layer: 50 nm | Image; table 1 | [35;36] |

| SS 304L | MP - UC - Anz | Anz: 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1 M H2O in EG (50 V at 5 °C for 15-60 mins) | for 60 min with & without stirring; Pore Dia: 65.9 & 63.0 nm; Thickness: 3.18 & 2.60 μm | Image; table 1 | [43] |

| SS 304 | UC- EP - Anz- HT | EP: Ethylene glycol monobutyl ether and HClO4 (6 V at 5 ℃ for 30 min) Anz: 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1 M H2O in EG; (80 V at 5 ℃ for 30 min) HT: 500 ℃ for two h | Honeycomb structure: 180-240 nm in diameter; Inner Pore Dia: 35 nm; Thickness: 1.65 μm; Compact/Barrier layer: 35 nm | Image; table 1 | [24;86;88] |

| SS 304 | UC - Anz - HT | Anz: 0.1 M NH4F and 0.1 M H2O in EG (50 V at 25℃) HT: 500 ℃ in air for two h | Avg Pore Dia: 43 nm; Thickness: 4.25 μm; Compact/Barrier layer: 107 +/-5 nm | Image; table 1 | [39] |

Mechanical polishing (MP) and ultrasonic cleaning (UC) are commonly used as pre-processing steps before anodization (Anz). However, electropolishing (EP) has also emerged as an alternative, eliminating the need for mechanical polishing [86,87]. As observed by Vignal et al. [27], electropolishing facilitates the formation of well-ordered pores with minimal oxide growth, serving as an ideal base for achieving highly structured anodized surfaces. Additionally, some studies have reported a two-step anodization process, where the initially formed oxides are selectively dissolved to create a patterned morphology. This patterned surface is a template for achieving more ordered structures during the second anodization step [38]. In the following sections, we will discuss the factors influencing pore morphology.

4. Factors influencing nanopore formation on stainless steel

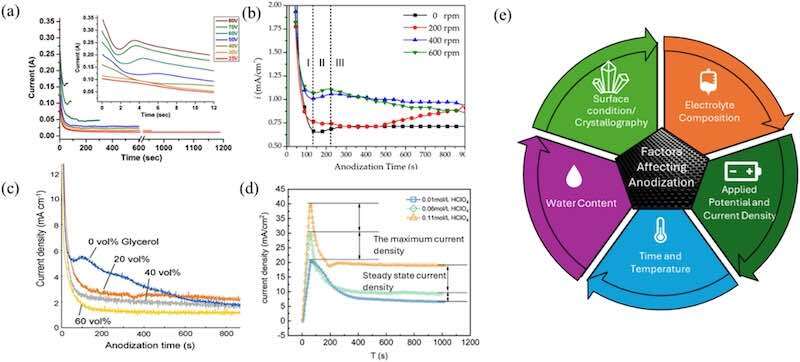

The morphology and quality of anodic oxide films on stainless-steel substrates are determined by a complex interplay of electrochemical and thermodynamic variables. Parameters such as electrolyte composition, applied voltage, current density, anodization duration, temperature, and water content strongly affect the balance between oxide growth and dissolution, which governs pore formation and stability [75,89]. These factors significantly influence pore morphology, dimensions, ordering, and stability, ultimately affecting the overall functionality of the resulting oxide films. Fig. 4 shows current density-time curves for 304 L stainless steel (SS) anodization under varying voltages, stirring speeds, electrolyte concentrations, and a schematic of key anodization factors. Low temperatures and organic electrolytes reduce ionic mobility, lowering steady-state currents [90]. Fluoride-rich electrolytes or higher concentrations of perchloric acid typically increase dissolution rates, raising both maximum and steady-state current densities. Additionally, adjustments in stirring speed enhance electrolyte homogeneity, which affects the current density response [43]. This section will discuss how these factors collectively dictate the balance between oxide growth and dissolution, controlling pore formation, as represented in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4. Current density-time curves for anodization of 304 L stainless steel under various experimental conditions: (a) increasing applied voltage at room temperature, (b) varying stirring speeds in ethylene glycol- NH4F-H2O electrolyte at 50 V, and (c-d) changing electrolyte concentration. The accompanying schematic summarizes the key anodization factors that affect pore formation.

![Fig. 5. Various factors influencing anodic pore morphology: (a-b) Significant variations in the voltage-time plot and corresponding microstructures for different organic electrolytes; (c-d) Current density-time curves alongside surface morphology changes with increasing voltage and anodization time; (d) Effect of increasing water content, showing notable voltage variations beyond 0.3 M; and (e) A plot demonstrating that the impact of water content on morphology variation is more pronounced compared to other factors[38,40,32,75],.](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/5.jpg)

Fig. 5. Various factors influencing anodic pore morphology: (a-b) Significant variations in the voltage-time plot and corresponding microstructures for different organic electrolytes; (c-d) Current density-time curves alongside surface morphology changes with increasing voltage and anodization time; (d) Effect of increasing water content, showing notable voltage variations beyond 0.3 M; and (e) A plot demonstrating that the impact of water content on morphology variation is more pronounced compared to other factors[38,40,32,75],.

4.1. Electrolyte composition

Electrolyte chemistry is the most critical factor controlling nanopore initiation and growth. Organic electrolytes based on ethylene glycol or glycerol, containing ammonium fluoride (NH4F), are commonly used because they provide high viscosity and controlled ionic mobility[45]. Fluoride ions, having high charge density and small ionic radii, facilitate the localized dissolution of metal oxides, enabling self-organized pore development by forming soluble metal-fluoride complexes[34]. For example, adding 0.1 M NH4F to ethylene glycol yields uniform nanopores on SS304 with diameters of 50–150 nm [35].

The amount of water in the electrolyte regulates oxide solubility and ionic conductivity. Excess water (>3 vol %) accelerates dissolution and suppresses oxide formation [36], whereas low water content (<0.1 mol L⁻¹) leads to unstable voltage fluctuations and irregular pores. Optimum nanopore ordering typically occurs at 0.3–0.5 mol l-1 H2O.

Alternative electrolytes such as sodium dihydrogen phosphate or sodium silicate have also been tested. These can reduce fluoride-related toxicity and, in some cases, improve corrosion resistance, though the resulting films are generally thinner (<100 nm) [38]. Thus, a balanced fluoride concentration in an organic solvent remains the most effective approach for producing thick, ordered nanoporous oxides [43].

4.2. Applied voltage and current density

The applied potential directly determines pore geometry through its influence on the electric field across the oxide barrier. Increasing voltage enlarges both pore diameter and interpore distance because of the higher field strength and enhanced ion migration[41,91]. Typical anodization voltages of 30–60 V yield pores of 80–130 nm with depths up to a few micrometers.

Excessively high voltages or current densities (>100 mA cm-2) can destabilize the oxide layer, causing field-assisted dissolution and surface breakdown [28]. Conversely, too low a voltage produces a compact barrier layer without porosity. Stable pore formation is usually achieved within moderate ranges of 20–60 V and 25–75 mA cm-2, where growth and dissolution remain balanced.

The electric-field strength across the barrier layer also evolves as the oxide thickens, strongly influencing pore morphology. Wang et al. [39]. demonstrated that during constant-potential anodization, the increasing oxide resistance reduces the effective field, causing the pore diameter to narrow from top to bottom until the voltage falls below the anodizing threshold (Fig. 6a). To overcome this limitation, a step-potential anodization method was employed, increasing the voltage in 5 V increments (50–70 V) to maintain a constant field. Each voltage step produced a brief current spike before stabilizing (Fig. 6b). The resulting oxide film, approximately 17 µm thick, comprised five well-defined layers with controlled pore dimensions (Fig. 6c). High-magnification SEM images (Figs. 6d–g) showed slight pore widening at layer boundaries followed by gradual shrinkage, confirming that voltage tailoring can sustain a uniform field and enable precise control of pore size and film thickness.

![Fig. 6. Evolution of pore size during anodization: (a) Schematic comparison of constant potential anodization and multi-step potential tailoring anodization. (b) Current transient curves correspond to the multi-step potential tailoring approach. (c) Cross-sectional SEM image of the resulting nanostructure. (d-g) High-magnification SEM images of four distinct boundaries, corresponding to the marked regions in (c). Images have been reproduced and modified with permission from the publisher[39].](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/6.jpg)

Fig. 6. Evolution of pore size during anodization: (a) Schematic comparison of constant potential anodization and multi-step potential tailoring anodization. (b) Current transient curves correspond to the multi-step potential tailoring approach. (c) Cross-sectional SEM image of the resulting nanostructure. (d-g) High-magnification SEM images of four distinct boundaries, corresponding to the marked regions in (c). Images have been reproduced and modified with permission from the publisher[39].

4.3. Anodization time

Anodization duration controls oxide thickness and pore depth. Short times (5–10 min) generate shallow nanopores (<20 nm), whereas extended anodization (15–30 min) yields deeper, better-defined structures. Beyond an optimum duration, further exposure leads to wall thinning and collapse due to continuous dissolution at the pore bases. Therefore, process optimization is required to maintain structural integrity and prevent over-etching [82].

4.4. Temperature

Temperature affects both ionic mobility and dissolution kinetics. Lower temperatures (0–10 °C) favor uniform oxide growth by suppressing chemical dissolution and thermal stress, resulting in more ordered nanopores [44]. At room temperatures (>25 °C), increased ion mobility accelerates oxide dissolution, producing irregular and unstable structures [36]. Very high temperatures (160 °C and above) in glycerol-based electrolytes led to rapid oxide dissolution and instability [45]. For most organic-based electrolytes, near-ice-bath conditions (5–10 °C) are ideal for stable self-organization.

4.5. Water content

Water acts as both a reactant and a conductivity enhancer in organic electrolytes. Moderate water content ensures sufficient oxygen supply for oxide formation while limiting excessive dissolution. Studies indicate that 0.3–0.5 mol l-1 water achieves the most consistent voltage behavior and morphology [75]. Too little water causes dielectric breakdown, while too much promotes rough, non-uniform dissolution. Precise control of hydration is therefore essential for reproducibility.

4.6. Crystallographic orientation

The crystallographic orientation of stainless steel has a decisive effect on oxide nucleation, pore morphology, and growth kinetics during anodization. Each grain orientation presents distinct atomic packing, surface energy, and dissolution behavior, which together govern local electric-field distribution and ion transport.

Studies on pure iron and stainless steels have shown that low-index planes behave very differently under anodic polarization. Fadillah et al. reported that Fe (100) requires roughly 30 % more charge than (110) or (111) to reach a comparable oxide thickness and tends to produce crystalline Fe2O3·FeF2 films, while (110) and (111) planes yield amorphous Fe3O4·FeF2. These variations arise from differences in atomic density and diffusion pathways within each orientation, which control cation migration under the applied electric field [92]. Li et al. prepared vertically aligned iron-oxide nanotubes by a three-step anodization at 50 V in fluoride-containing electrolyte, followed by annealing between 200 and 600 °C. The amorphous nanotubes transformed into nanoplates and nanoflakes at 400–500 °C, while incorporated F⁻ ions stabilized hematite along the [110] axis, promoting single-crystal-like growth [93]. These results show that both orientation and post-treatment conditions govern the crystallinity and morphology of anodic oxides: the (100) facet favors direct crystalline film formation, whereas (110) structures can achieve comparable stability through fluoride incorporation and thermal activation.

Yuehua et al. demonstrated that austenitic stainless steel with a face-centered-cubic (FCC) lattice develops orientation-dependent surface textures during anodization [94]. The (111) facets tend to form ordered 45° grooves, whereas body-centered-cubic (BCC) regions display wedge-like features. Atomic-force-microscopy (AFM) images show that these patterns arise from differences in cleavage energy among crystal planes, with easily cleaved orientations dissolving faster and thus defining regular groove patterns. Fig. 7 illustrates these surface transformations with anodization time and crystal orientation.

![Fig. 7. Surface morphology and cross-sectional SEM images of porous anodic films formed on (a, d) Fe (100), (b, e) Fe (110), and (c, f) Fe (111) single crystals anodized at 60 V in mono-ethylene glycol containing 1.5 M H₂O and 0.1 M NH₄F. The right panel depicts stainless-steel surfaces forming orientation-dependent grooves after anodization for 30 and 120 mins, while the lower section illustrates structural evolution of anodized iron oxide, from nanotubes to nanoplates, nanoflakes, and compact films, with increasing annealing temperature (100–600 °C). Images reproduced and modified with permission from the publishers[94].](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/7.jpg)

Fig. 7. Surface morphology and cross-sectional SEM images of porous anodic films formed on (a, d) Fe (100), (b, e) Fe (110), and (c, f) Fe (111) single crystals anodized at 60 V in mono-ethylene glycol containing 1.5 M H₂O and 0.1 M NH₄F. The right panel depicts stainless-steel surfaces forming orientation-dependent grooves after anodization for 30 and 120 mins, while the lower section illustrates structural evolution of anodized iron oxide, from nanotubes to nanoplates, nanoflakes, and compact films, with increasing annealing temperature (100–600 °C). Images reproduced and modified with permission from the publishers[94].

The relationship between crystal orientation and anodic pattern formation can be rationalized by the interplay of electrochemical and mechanical factors. These include variations in surface energy and charge density that alter local field intensity, anisotropic diffusion pathways that direct ion migration, orientation-dependent stress accumulation during oxidation, and preferential adsorption of electrolyte species that modulate local dissolution rates. Collectively, these effects determine the nucleation density, directionality, and ordering of nanopores.

Pattern formation may also originate from orientation-dependent behavior during electropolishing, which is often used before anodization. Yuzhakov et al. [94]. showed that differential adsorption of organic species and field gradients on specific facets can generate striped or hexagonal patterns with characteristic wavelengths near 100 nm. These pre-existing textures act as templates for subsequent pore initiation, enhancing long-range order during anodization.

A broader crystallographic framework proposed by Sun et al. further clarifies the link between lattice structure and anodic morphology [95]. Their comparative study revealed that metals with an FCC structure, such as stainless steel and aluminum, readily form highly ordered porous oxides, while hexagonal-close-packed (HCP) metals tend to develop nanotube arrays, and BCC metals generally produce less ordered porous films. This perspective supports the experimental trends described above and provides a tretical basis for designing ordered porous metal-oxide architectures through controlled anodic oxidation.

In summary, crystallographic orientation dictates both the thermodynamic stability and kinetic evolution of anodic oxides. Controlled texturing through electropolishing, rolling, or epitaxial deposition offers promising routes to achieve reproducible, orientation-guided nanostructures. A deeper understanding of orientation-dependent oxidation and dissolution behavior will be essential for tailoring anodized stainless-steel surfaces for advanced functional and corrosion-resistant applications.

Optimization of anodization parameters, particularly electrolyte composition, voltage, temperature, and substrate orientation, enables precise control over nanopore morphology and oxide stability. The interplay of crystallographic orientation, doping, and thermal treatment ultimately dictates pore ordering and phase evolution, providing a framework for designing reproducible, high-performance anodized stainless-steel surfaces. To summarize the quantitative influence of key anodization parameters on oxide morphology and corrosion performance, Table 3 presents a consolidated correlation between process variables, structural features, and representative electrochemical indicators.

Table 3. Quantitative correlation between anodization parameters and resulting oxide characteristics and performance of stainless steels. Note: a) icorr measured in 3.5 wt % NaCl; (b) Pore size estimated from SEM; (c) Values after annealing unless specified. Abbreviations: EG – ethylene glycol; EP – electropolishing; UC – ultrasonic cleaning; MP – mechanical polishing.5. Recent Advances in Nanoporous Oxide Structures.

| Parameter | Typical experimental range | Structural/morphological effect | Quantitative trends & representative data | Performance indicator (icorr; stability; etc.) | References |

| Electrolyte composition (NH4F-H2O-EG/glycerol system) | 0.05–0.2 M NH4F with 0–0.5 M H2O in EG or glycerol | F- promote pore nucleation; H2O: oxide solubility and conductivity | 0.1 M NH4F + 0.15 M H2O → uniform pores (40–150 nm); > 0.5 M H2O → rough; unstable surface; < 0.1 M H2O → field instability (branching) | Uniform films; icorr ∼ 0.02 µA cm-2; | [34;36;42;75;96] |

| Applied voltage | 30–90 V (practical EG systems) | Determines field strength; pore geometry; oxide thickness | Pore Dia ∼ 1.0–1.2 nm V-1; 30–70 V → ordered pores (60–100 nm); > 80 V → transpassive dissolution / irregular pitting | Low V (30–40 V) gives dense films and lower icorr; > 80 V → oxide breakdown and Fe/Ni leaching | [32;37;79] |

| Anodization time | 5–60 min | Controls pore depth and wall stability | Thickness rises rapidly ≤ 20 min then saturates; > 45 min → wall thinning/ collapse; 60 min at 40 V → ∼ 3 µm film; | 15–30 min → uniform 2–3 µm pores and low icorr; longer time reduces Epit | [32;43;79] |

| Temperature | 0–25 °C (EG systems); | Influences dissolution rate and ordering | Low T (0–10 °C) → ordered pores (∼70–90 nm); > 25 °C → irregular morphology; > 40 °C → pitting and loss of self-organization | Films formed ≤ 10 °C show the lowest icorr; high T reduces ordering and corrosion stability | [42;75] |

| Surface pre-treatment | MP / UC / EP / Two-step patterning | Determines pore initiation uniformity and film adhesion | Electropolishing(EP) smooths the substrate for uniform pore formation. Two-step anodization imprints dimple templates for ordered arrays | EP reduces defect density and improves adhesion. Two-step films show higher capacitance and stability | [38;40;44] |

| Electrolyte medium | EG vs. Glycerol vs. Mixed EG/Glycerol | Solvent viscosity affects field distribution and aspect ratio | Glycerol permits higher stable voltages (≤ 100 V); EG favours uniform barrier films ≤ 60 V; EG + 20 % glycerol mix → best balance | Mixed solvent system gives high-aspect-ratio (> 5:1) pores without branching | [36;40] |

| Post-annealing / heat treatment | 400–773 K (2 h; air or N2) | Improves crystallinity and removes F- | Fe2O3; Cr2O3 Major pahses; ∼20 % thickness loss; oxide densification | icorr ↓ to < 0.02 µA cm-2; Epit ↑ > 200 mV; | [36;44;47] |

| Advanced control (step-potential anodization) | 50 → 70 V (step profile; one h) | Maintains a steady field; minimizes branching | Produces ultra-thick porous film > 17 µm with pore taper (53 → 34 nm); stable Cr-rich barrier and uniform field | For supercapacitors; mechanically coherent and corrosion-resistant | [39] |

The continuous development of anodization techniques has enabled the fabrication of increasingly ordered and multifunctional oxide films on stainless-steel substrates. Recent advances focus on improving pore uniformity, adhesion, and corrosion resistance through process innovation, surface pre-patterning, and hybrid treatments. Fig. 8 schematically illustrates the major anodization strategies discussed in this section. The progress in stainless-steel anodization has diversified into several advanced routes that differ in complexity, controllability, and achievable structure. The following subsections categorize these developments, ranging from process-based modifications such as dual-step anodization to high-energy and hybrid treatments, highlighting how each method contributes to improved ordering, functionalization, and corrosion resistance.

![Fig. 8. Schematics representing advanced anodization methods for developing nanoporous structures on stainless steels (a) Two-step anodization method, (b) anodization on pre-patterned surface, (c) Plasma electrolytic Oxidation, (d) Hydrophobic nanopores by chemical treatments, (e) Pd deposits on nanopores for enhanced catalyst activity, adapted from references[24,79,97,41,46],.](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/8.jpg)

Fig. 8. Schematics representing advanced anodization methods for developing nanoporous structures on stainless steels (a) Two-step anodization method, (b) anodization on pre-patterned surface, (c) Plasma electrolytic Oxidation, (d) Hydrophobic nanopores by chemical treatments, (e) Pd deposits on nanopores for enhanced catalyst activity, adapted from references[24,79,97,41,46],.

5.1. Dual-step anodization

This method, introduced for Aluminum anodization by Masuda et al. [98]. similarly used by Zhang et al. [38]., who first reported the two-step anodization method on stainless steel using Sodium dihydrogen phosphate solution. Recently, Yuga Osada et al. utilized a two-step anodization method for stainless steels in their work; a schematic is shown in Fig. 8(a). The process began with electropolishing austenitic stainless steel (JIS SUS304) in a glycerol solution containing phosphoric and sulfuric acids at 30 °C under a constant current, creating a smooth substrate surface [42]. The electropolished substrate was then anodized in an ethylene glycol solution with NH4F at 0 °C and 30–50 V for 15–120 min. Following the initial anodization, the anodic oxide film was removed by immersing the sample in a CrO3 and HF solution at 25 °C, leaving a patterned surface. A second anodization under identical conditions produced a nanohole array with uniformly sized and regularly arranged pores[79,99,100],.

While the dual-step anodization method improves pore ordering by reusing a pre-patterned surface generated in the first step, achieving large-area uniformity and precise control over pore distribution remains challenging. To overcome these limitations, subsequent research explored pre-patterning strategies that combine lithographic or mask-based techniques to define pore initiation sites more accurately.

5.2. Pre-patterning method

A repatterning method that combines porous alumina masks with anodization can achieve high-aspect-ratio nanohole arrays on stainless steel. This approach enables precise control over pore arrangement and morphology, offering potential for advanced material applications. Takashi Yanagishita et al. [41]. Demonstrated a pre-patterning method to achieve ordered nanopore structures on stainless steel using porous alumina masks. The masks, fabricated through a two-step anodization process of electropolished aluminum in sulfuric acid, featured an ordered hole arrangement, as shown in Fig. 8(b). After selectively dissolving the oxide layer formed during the first anodization, a second anodization and subsequent etching enlarged the pore size. These alumina masks were placed on electropolished 304 stainless steel and subjected to Argon (Ar) ion milling to transfer the hole pattern onto the substrate. The alumina mask was then removed through wet etching. The pre-patterned stainless steel was anodized in ethylene glycol containing ammonium fluoride, forming an oxide layer with a nanohole array. Dissolution of this oxide layer revealed a concave pattern corresponding to the ordered nanopore structure.

Although pre-patterning offers superior control over pore arrangement, it often involves complex and time-intensive processes, limiting scalability for industrial applications. In parallel, plasma-assisted anodization techniques have emerged as a promising route for achieving dense, adherent oxide layers with improved corrosion resistance and mechanical robustness.

5.3. Plasma-assisted anodization

Plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) is a surface modification technique that produces hard, dense, and corrosion-resistant oxide layers by applying a high voltage above the breakdown threshold, generating localized plasma discharges. While traditionally used to valve metals like aluminium and titanium, its application to non-valve metals such as stainless steel has faced challenges due to unstable oxide film formation [101]. Address this, Jun Heo and collaborators recently worked on a novel cathodic PEO (CPEO) method to enhance the corrosion resistance of austenitic stainless steel [102]. Unlike traditional PEO, where the substrate acts as the anode, CPEO configures the substrate as the cathode. This unique configuration addresses key challenges associated with anodic PEO on non-valve metals, such as the difficulty forming stable insulating films required for plasma discharges.

In CPEO, plasma discharge occurs due to gaseous bubbles formed on the cathode's surface during electrolysis. These bubbles function as transient insulating barriers, facilitating localized plasma generation when a high pulsed DC voltage is applied. The discharge allows the substrate's metal ions to participate directly in forming the oxide layer, resulting in strong adhesion and a composition tightly bonded to the substrate [103,104].

Jun Heo and team demonstrated this technique using glycerol-based electrolytes containing 0.5 M KCl, which provides the required conductivity [24]. The process was conducted at a low temperature (5 °C) to manage the heat generated by the discharges, with magnetic stirring to enhance heat dissipation (refer to the schematic in Fig. 8(c)). A pulsed DC voltage of 600 V, with a 10 % duty cycle and 100 Hz frequency, was applied for short durations (20–30 s). The rapid and controlled plasma events created a uniform and dense oxide coating that significantly improved the corrosion resistance of stainless steel. This method overcomes the adhesion and stability limitations of oxide layers formed using traditional PEO or chemical approaches, making CPEO a promising alternative for enhancing the surface properties of stainless steel in demanding environments.

While plasma-assisted anodization produces mechanically robust and corrosion-resistant oxides, its high-energy nature and limited control over fine pore geometry motivate the integration of hybrid processes. Recent studies have therefore combined conventional anodization with surface functionalization or composite layer design to tailor both structure and surface chemistry for multifunctional performance.

5.4. Hybrid and composite nanoporous oxide layers

Hybrid and composite nanoporous oxide layers have been explored to enhance functional properties. Lee et al. [88] developed a fluorocarbon lubricant-impregnated nanoporous oxide (FLINO) coating on stainless steel, enhancing corrosion resistance in both liquid and vapor phases. The FLINO layer significantly improves durability, offers self-healing properties, and provides superior atmospheric corrosion resistance, addressing a key challenge in corrosion-resistant coatings. In comparison, similar work by Manilal and his team[46] developed a method to enhance the corrosion resistance and hydrophobicity of SS 304 through controlled electropolishing, anodization, and functionalization with silane derivatives, as shown in Fig. 8(d). Using an ethylene glycol-based electrolyte containing ammonium fluoride, a well-ordered, hexagonally close-packed nanoporous oxide layer was achieved on SS 304 after anodization and annealing (AAS). Subsequently, self-assembled monolayers of silane molecules, octadecyl trimethoxy silane (ODTS) and perfluorooctyl triethoxy silane (PFTS), were deposited on the nanoporous oxide layer [46]. The hydrophobicity of the modified surfaces increased with silane concentration, yielding water contact angles of 127.6° for 0.50 wt. % ODTS and 128.83° for 0.50 wt. % PFTS.

Nanoporous stainless steel (NPSS), fabricated through anodization, has proven to be an effective substrate for electrocatalytic applications, highlighting its versatility as a support material. Zhan et al. [33]. deposited a TiO2/WO3 nanocomposite film on anodized stainless steel to optimize photocatalytic activity. Similarly, Behzad et al. [105]. demonstrated the creation of a self-organized nanoporous oxide layer on stainless steel with an average pore size of approximately 77 nm. These nanopores were modified using pulsed electrodeposition to selectively deposit copper within the pore structure Fig. 8(e). A subsequent galvanic replacement reaction between the deposited copper and a PdCl2 solution formed a Pd/Cu composite layer on the NPSS substrate, resulting in a porous, high-surface-area film with significantly reduced palladium loading while enhancing the electrochemically active surface area (EASA) to 173.4 cm²/mg. Electrochemical evaluations revealed that the porous structure and synergistic interaction between Cu and Pd enhanced catalytic activity and stability. This strategy optimized noble metal utilization and improved reaction kinetics and poisoning tolerance, positioning NPSS/Cu/Pd electrodes as promising candidates for fuel cells and sensor technologies. The tuneable nature of NPSS underscores the potential of anodization in designing cost-effective and sustainable catalytic systems and enhanced corrosion resistance[106,107].

Together, these recent advances demonstrate a clear evolution from simple anodization methods to sophisticated, multi-step or hybrid approaches that enable precise morphological control, enhanced mechanical integrity, and multifunctional behavior. The summarized comparison in Table 4 highlights the strengths, limitations, and suitability for application of each technique, providing a holistic view of current progress and remaining challenges.

Table 4. Summary of the advanced methods, limitations, and industrial scope for developing nanostructured oxide surfaces on stainless steel.

| Strategy | Mechanism | Benefits | Limitations | Application Note / Industrial Scope | Ref. |

| Conventional single-step anodization | Direct DC anodization in NH4F-H2O-EG electrolytes | Simple setup; controllable oxide thickness | Limited pore ordering; cracking in thick films | General corrosion-protection coatings and decorative layers; scalable batch process | |

| Two-Step Anodization | Re-anodization after oxide removal | Improved pore ordering; better adhesion | Additional processing steps | Uniform nanopore arrays for sensors and photoelectrodes; laboratory to pilot scale | |

| Pre-patterning | Top-down surface texturing | Precision nanostructures | Costly; less scalable | MEMS templates and nano-molds; small-area fabrication | [41] |

| Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation (PEO) | High-voltage arc-induced growth | Hard; crystalline coatings | Rough surface; energy-intensive | Dense wear- and corrosion-resistant films on large components; industrially mature | |

| Hybrid Techniques | Layered / combined processes | Tunable performance | Complex workflows | Solar water splitting; catalysis; and antibacterial surfaces. | [106;107] |

| Step-potential / tailored anodization | Sequential voltage ramp maintaining field uniformity | Thick; uniform oxide with graded pores | Requires programmable control | High-surface-area electrodes and functional coatings; scalable to continuous lines |

6. Applications for nanoporous oxide structures

The development of nanoporous oxide layers on stainless steels has opened opportunities for integrating corrosion protection with functional performance in diverse technological domains. The ability to control oxide thickness, porosity, and composition allows these materials to serve not only as passive barriers but also as active interfaces for electrochemical and catalytic processes. The major application areas are summarized below.

6.1. Corrosion resistance

The corrosion protection provided by anodized stainless steel strongly depends on structural and compositional attributes, including oxide thickness, crystallinity, and defect density. Anodized oxide films, typically 100 nm to several micrometers thick, significantly surpass the protective capability of the thin (2–5 nm) native passive film, primarily composed of amorphous Cr2O3 [44,75,111]. Anodically grown films incorporate complex oxide structures, including Cr-rich oxides (Cr2O3), iron oxides (Fe2O3, Fe3O4), nickel oxides (NiO), molybdenum oxides (MoO3), oxyhydroxides (FeOOH), and spinel-type phases (FeCr2O4, NiFe2O4) depending on electrolyte composition, anodization parameters, and subsequent annealing [35,36,38]. Fig. 9(a-c) shows polarization curves for anodized and bare stainless steel in 0.1 M H2SO4, NaCl, and NaOH. Anodized samples exhibit higher current densities in acid due to active porous oxides, improved pitting resistance in chloride, and a more stable passive region in alkaline media, demonstrating the influence of anodic oxides on corrosion behaviour [112].

![Fig. 9. (a) Contact angles of anodized SS316L before FDTS coating at 30, 50, 70, and 90 V. (b) Hydrophilic (wetted) state of the nano-oxide surface. (c) Contact angles after FDTS coating. (d) Hydrophobic (dewetted) state of the nano-oxide surface. (e) PDP curves of bare and FDTS-coated anodized SS316L at different voltages. Images reproduced and modified with permission from the publisher[118,46],.](/images/images/whitepapers/anodizationStainlessSteels/9.jpg)

Fig. 9. (a) Contact angles of anodized SS316L before FDTS coating at 30, 50, 70, and 90 V. (b) Hydrophilic (wetted) state of the nano-oxide surface. (c) Contact angles after FDTS coating. (d) Hydrophobic (dewetted) state of the nano-oxide surface. (e) PDP curves of bare and FDTS-coated anodized SS316L at different voltages. Images reproduced and modified with permission from the publisher[118,46],.

A crucial feature for corrosion resistance is the formation of a compact Cr-rich inner barrier (∼50–60 nm thick), which prevents ionic transport and inhibits pitting initiation. While nanoporous outer structures enhance surface functionality, the underlying dense layer is critical to corrosion protection; if compromised, pores become pathways for aggressive ions [45]. Consequently, anodized films are often annealed (300–700 °C) to convert amorphous or hydrated oxides into dense, crystalline phases. Crystalline oxides exhibit enhanced mechanical and electrochemical stability, significantly reducing corrosion current density (icorr) and increasing polarization resistance (Rp).

Annealing-induced phase transformations within iron oxides are accompanied by density and lattice-parameter changes that generate internal stresses within the anodic film. In particular, the transformation of magnetite (Fe3O4, cubic spinel) to hematite (α-Fe2O3, rhombohedral corundum) involves structural rearrangement and a reduction in molar volume [[113], [114], [115]]. This mismatch, combined with constraints imposed by the substrate, produces tensile stresses that can exceed the oxide’s cohesive strength, resulting in microcrack formation and local delamination. Similar transformation-related stress effects have been widely reported for thermally grown iron-oxide scales on steels, where phase evolution, differential thermal expansion, and interface bonding collectively determine the stress distribution within the oxide layer [116,117].

During initial anodization, stress may be accommodated by pores without causing visible cracks. However, upon annealing, after pore formation, this shrinkage can cause cracking or delamination due to limited mechanical flexibility, negatively affecting surface integrity and barrier performance [39,75].

Quantitative electrochemical data confirm the superiority of dense crystalline oxide structures. For example, anodized and annealed 316 L stainless steel showed a 72.2 % corrosion inhibition efficiency, reducing corrosion current (icorr) from 0.133 μA/cm2 (bare) to 0.037 μA/cm2 in 3.5 % NaCl, with significantly reduced corrosion depths compared to untreated materials[47]. Similarly, 304 stainless steel anodized and annealed at 500 °C showed a decrease in icorr from 0.20 μA/cm2 to 0.02 μA/cm2 and a polarization resistance increase from 13 to 120 kΩ·cm² after 14 days in artificial seawater [44]. Lubricant-impregnated anodized films further decreased icorr by nearly two orders of magnitude, providing exceptional stability in aggressive hydrochloric acid solutions. However, if not thermally treated, anodized films rich in amorphous or fluoride-containing phases exhibited rapid degradation and higher corrosion rates in acidic media.

Nanoporous oxide layers formed by anodization on stainless steel exhibit pronounced hydrophilicity due to surface hydroxyl groups and nanoscale roughness, which enhance water spreading and promote rapid oxide formation. However, this high wettability can also facilitate the accumulation of moisture and aggressive ions, increasing the risk of localized corrosion. Interestingly, the hydrophilic nature of these surfaces is advantageous for biomedical applications, such as implants, where enhanced cell adhesion and growth are desirable. Hydrophobic modification using FDTS coating transforms these surfaces to superhydrophobic, as seen by contact angles increasing from 57.4° at 30 V to 141.4° at 90 V. This transition greatly enhances corrosion resistance by trapping air in the pores and blocking chloride ingress, achieving over 96 % prevention efficiency (Fig. 9).

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) consistently highlights improved barrier properties in dense, annealed oxides, showing elevated charge transfer resistance (Rct) and reduced double-layer capacitance (Cdl), indicating lower electrochemical activity and enhanced passivation [74,75]. Yet, the stresses arising from the phase transformations represent a notable challenge that may offset these gains if mechanical integrity is compromised.

To maximize long-term durability, careful control of anodization parameters (e.g., moderate voltage, low water-content electrolytes), post-anodization annealing, and possibly additional surface treatments (hydrophobic or lubricant coatings) are essential. Future research should prioritize clarifying relationships between oxide phase transformations, associated mechanical stresses, and resulting corrosion performance. Standardized long-term immersion studies and advanced mechanical characterization (adhesion, hardness, fracture resistance) are needed to bridge existing knowledge gaps and better predict real-world durability.

In summary, the corrosion protection provided by anodized stainless steel is fundamentally dependent on oxide thickness, composition, crystallinity, and defect management. Annealing-induced phase transformations, while beneficial in enhancing crystallinity and reducing corrosion rates, carry significant risks associated with volume shrinkage and stress-induced cracking.

6.2. Energy conversion and photocatalysis

Anodized stainless steel surfaces enriched with iron oxides, particularly Fe2O3 (hematite) and Fe3O4 (magnetite), are increasingly investigated for their role in solar-driven photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting and other photocatalytic processes. The unique semiconducting nature of hematite, with a direct bandgap of approximately 2.1 eV, enables efficient absorption of visible light, making it an up-and-coming candidate for hydrogen production through solar energy conversion [29,119]. The abundance, low cost, and robust chemical stability of hematite in aqueous environments further position it as a scalable solution for large-area energy applications. Through anodization, stainless steel surfaces can be engineered to form nanoporous oxide morphologies, significantly enhancing the active surface area and simultaneously shortening the diffusion paths for photogenerated carriers. This nanostructuring not only facilitates effective charge separation but also improves quantum efficiency and photocurrent response under operational conditions [120]. For instance, studies such as those by Jaimes et al. have reported that anodized stainless steel substrates with hematite coatings yield hydrogen evolution rates that are two to three times higher than those achieved with flat, non-nanostructured films, with measured steady-state photocurrent densities in the range of 0.4 to 0.8 mA/cm2 under AM1.5 simulated solar illumination and incident photon-to-current efficiencies (IPCE) around 1.2 % at 400 nm, which represents approximately double the value seen in compact oxide films [40,43,121].